Finding a Limit to Evolution?

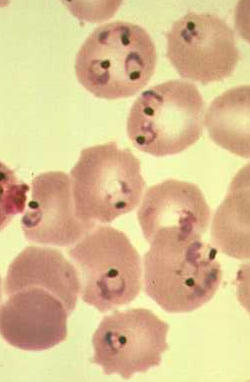

In his 2007 book, The Edge of Evolution, Behe argued that evolutionary change has a limit, an “edge,” beyond which it cannot go. To put some hard numbers on that edge, he used the evolution of chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium, the malarial parasite, as a prime example of the best that evolution can do. Noting that chloroquine resistance has arisen only rarely since the drug was introduced in 1947, Behe estimated that the probability of a single cell becoming resistant to the drug was just 1 in 1020. He called any series of mutations equal to the complexity of chloroquine resistance a “CCC” (chloroquine complexity cluster), and used that 1 in 1 in 1020 number to argue that the probability of two mutations of CCC’s complexity emerging was the square of that probability, or 1 in 1 in 1040. That, he told us, was beyond the ability of Darwinian evolution to achieve. Therefore, any time we see two or three mutations or adaptations similar to a CCC in an organism, the only possibility is that they were “designed.”

Figure 2: (Left) Michael Behe’s 2007 book,The Edge of Evolution. (Right) Light micrograph of red blood cells infected with Plasmodium, the malaria parasite.

When it appeared in 2007, Behe’s book was roundly criticized by reviewers in Science, Nature, and the New York Times. So why does he now feel he can claim vindication? He does this by pretending that the criticisms of his book were based on nothing more than that 1 in 1020 probability. According to Behe’s July 14, 2014 web posting, the new research study shows, “that the need for an organism to acquire multiple mutations in some situations before a relevant selectable function appears is now an established experimental fact.” That was, of course, an established experimental fact long before Behe read the PNAS paper, but never mind.

Apparently emboldened a week later, on July 21, 2014 he posted an open letter challenging his critics (myself included) to dispute that 1 in 1020 probability for a CCC. As he put it, “Talk is cheap. Let’s see your numbers.” Such language implies, of course, that these multiple critiques were based on Behe’s numbers. But they weren’t. The problem was not, as Behe now tries to claim, that anyone disputed the odds of developing resistance to chloroquine. Behe’s arguments about an “Edge” to evolution were wrong for a far more fundamental reason. But first, let’s look at how badly he misrepresented that PNAS paper in an effort to claim vindication.

< Previous ...... Next >