|

|

|

|

"The relief prayed for is granted." With

those words, on January 5, 1982, Federal Judge William K. Overton struck

down a state law that would have mandated the teaching of creation-science

in the public schools of Arkansas. Overton's decision followed an extraordinary

public trial in which a series of scientific heavyweights, including Harvard's

Steven J. Gould, persuasively argued in court that "creation-science"

was a religious idea that did not meet the generally-accepted tests for

scientific theory. As such, the Arkansas creation-science law had the primary

effect of advancing a religion in the public schools, and was invalidated

under the First Amendment's clause prohibiting establishment of religion.

A similar law in Louisiana was invalidated shortly thereafter. Case closed?

Not at all.

There is a new movement to counter the teaching of evolution in the schools,

and it claims to be based on a non-religious critique of evolution. In many

respects, the anti-evolution crusades of the 80s may have failed because

they were aimed too high at State Boards of Education and Legislatures.

The public pressure was obvious, easily recognized, and quickly invalidated

by court orders and scientific counterattacks. This time the opponents of

evolution have targeted a campaign at the grassroots at local school boards

and it looks like they are having some success.

In September of 1993, an

anti-evolution majority of newly elected board of education members in Vista,

California voted to implement a "creation-science" component as

part of their biology curriculum. The science teachers of the district were

critical of the decision, and their textbook selection committee flatly

rejected a book put forward to support anti-evolution teachings. Backing

down only slightly, the elected local board has now instructed the schools

to include "discussions of divine creation " at "appropriate

times" in the social science and language arts curricula. Similar actions

have been urged upon scores of school boards around the country, and in

some places, challenges to evolution are already part of the standard curriculum.

Since 1986, for example, the school board of Louisville, Ohio, has directed

its teachers to teach "alternate theories to evolution" The centerpiece

of these challenges to evolution is something that has become known as "intelligent

design theory."

In September of 1993, an

anti-evolution majority of newly elected board of education members in Vista,

California voted to implement a "creation-science" component as

part of their biology curriculum. The science teachers of the district were

critical of the decision, and their textbook selection committee flatly

rejected a book put forward to support anti-evolution teachings. Backing

down only slightly, the elected local board has now instructed the schools

to include "discussions of divine creation " at "appropriate

times" in the social science and language arts curricula. Similar actions

have been urged upon scores of school boards around the country, and in

some places, challenges to evolution are already part of the standard curriculum.

Since 1986, for example, the school board of Louisville, Ohio, has directed

its teachers to teach "alternate theories to evolution" The centerpiece

of these challenges to evolution is something that has become known as "intelligent

design theory."

Intelligent design has been embraced by critics of evolution around the

country who are eager to find an seemingly non-religious alternative to

the teaching of evolution. Intelligent design is the modern synthesis of

a classic argument that an engineer would love. Quite simply, it states

that living organisms are the product of careful and conscious design. A

close examination of living organisms, so the argument goes, reveals details

of structure and physiology that cannot be accounted for by the workings

of evolution. Therefore, these organisms must be the products of design.

The Argument from Design

If you were walking through the woods, and saw two objects lying on the

ground, a stone and a pocket watch, what would your first thoughts be? Suppose

a companion asked you where the stone and the pocket watch had come from?

You might well have laughed as you answered that for all you knew, the stone

had been there forever. It's safe to say, however, that you would

not have given that answer concerning the watch. It could not have been

there forever, for the very simple reason that it was produced by a watch-maker,

and watch-makers have not existed forever. Every gear, spring, and

screw in a watch is evidence of the fact that watches are not natural objects

that have existed forever. Rather, they have been produced by the conscious

design and handiwork of watch-makers.

In 1802, Rev. William Paley of Carlisle made that argument in his book Natural

Theology. As you might suspect, watches and stones were not the real

objects of his interest, for Paley was concerned with a timeless question

that still rivets our attention nearly two centuries later. With all of

its astonishing variety, complexity, and diversity, did life itself have

a designer? To Paley, the answer was clear.

... "There cannot be design without a designer; contrivance without

a contriver ... The marks of design are too strong to be got over. Design

must have had a designer. That designer must have been a person. That person

is GOD. "

Paley's writings form one of the most lucid examples of a train of reasoning

known as the "Argument from Design." In various forms, it has

served for centuries as a classic argument for the existence of God, and

more recently, as a counter-argument for a very different explanation of

the diversity of living species. That alternative explanation was advanced

more than 50 years after Paley by his countryman, Charles Darwin. Darwin's

"abstract" of his work, On the Origin of Species, was an

instant scientific and popular sensation. The theory of evolution, as Darwin's

ideas have come to be known, accounts for the origin of living species in

ways that could not be more different from those of William Paley. In Darwin's

world, living things did not have a conscious, intelligent designer. Instead

of being designed, their exquisite adaptations and specializations were

the products of natural selection, acting on the raw materials of variation

and genetic change.

Paley's argument for conscious design was well known to Darwin, and he answered

it effectively, showing that natural selection could account for many of

the classic examples of structures and organs that were thought to demand

conscious design. But Darwin did not put the argument from design to rest.

Far from it. The modern advocates of this argument now clamor for a place

in the science classroom under the banner of "intelligent design theory."

In fact, a modern restatement of the argument is found in the book Of Pandas

and People by Percival Davis & Dean Kenyon. This well-illustrated 170

page text is the very book rejected by Vista's science teachers in 1993.

Despite this recent setback, Of Pandas and People is often put forward as

an example of how intelligent design might be placed in the biology classroom.

The book argues that "In creating a new organism, as in building a

new house, the blueprint comes first. We cannot build a palace by tinkering

with a tool shed and adding bits of marble piecemeal here and there. We

have to begin by devising a plan for the palace that coordinates all the

parts into an integrated whole. Darwinian evolution locates the origin of

new organisms in material causes, the accumulation of individual traits.

That is akin to saying the origin of a palace is in the bits of marble added

to the tool shed. Intelligent design, by contrast, locates the origin of

new organisms in an immaterial cause: in a blueprint, a plan, a pattern,

devised by an intelligent agent. "

Of all the arguments that have been advanced against evolution, intelligent

design is the most appealing, most common, and in my view, the most effective.

The reasons should be obvious. First, the argument is easy to make and easy

to understand. Second, the argument appeals to the emotional sense that

we, and other living things, are what we are and where we are as the conscious

result of intelligent design. Third, and most telling, the argument seems

strengthened by each advance in our understanding of the complexity of life.

The grander the palace, the greater the leap of imagination that is required

to imagine that it could have been constructed by "tinkering with a

tool shed."

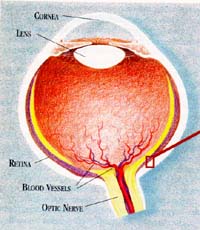

I would not argue, even for a minute, that living organisms are not complex

or intricate. In fact, I'd claim that even William Paley underestimated

the complexity of living organisms by several orders of magnitude. One case

in point is a structure often cited as a perfect example of intelligent

design: the human eye. Indeed, the eye is often compared to a camera, but

such comparisons are unfair. The eye is better than any camera.

Like a top-of-the-line

modern camera, the eye contains a self-adjusting aperture, and an automatic

focus system. Like a camera, its inner surfaces are surrounded by dark pigment

to minimize the scattering of stray light. However, the sensitivity range

of the eye, which gives us excellent vision in bright sunlight as well as

in the dimmest moonlight, far surpasses that of any film. The neural circuitry

of the eye produces automatic contrast enhancement and sensitivity to motion.

Its color analysis system enables it to quickly adjust to lighting conditions

(incandescent, fluorescent, and sunlight) that would require a photographer

to change film or add filters.

Like a top-of-the-line

modern camera, the eye contains a self-adjusting aperture, and an automatic

focus system. Like a camera, its inner surfaces are surrounded by dark pigment

to minimize the scattering of stray light. However, the sensitivity range

of the eye, which gives us excellent vision in bright sunlight as well as

in the dimmest moonlight, far surpasses that of any film. The neural circuitry

of the eye produces automatic contrast enhancement and sensitivity to motion.

Its color analysis system enables it to quickly adjust to lighting conditions

(incandescent, fluorescent, and sunlight) that would require a photographer

to change film or add filters.

Finally, the eye-brain combination produces depth perception that is still beyond the range of an camera or video system. Just ask your local photo or video engineer to design a system that will calculate, from a snapshot, the exact force required to sink a basket, on the run, from 25 feet away. Charles Barkley and his NBA colleagues perform such calculations with astonishing regularity, all based on the information that their eyes acquire in a split second glance at the basket.

The argument from design asserts that the combination

of nerves, sensory cells, muscles, and lens tissue in the eye could only

have been "designed" from scratch. It would be too much, the argument

goes, to ask evolution, acting on one gene at a time, to assemble so many

interdependent parts. After all, how could evolution start with a sightless

organism and produce a retina, which would itself be useless without a lens,

or a lens, which would be useless without a retina? As Paley himself wrote:

"Is it possible to believe that the eye was formed without any regard

to vision; that it was the animal itself which found out, that, although

formed with no such intention, it would serve to see with?"

Complex physiological systems are not the only cases to which the argument

from design can be applied. One might well ask whether the careful and precise

movements of cells and tissues during human embryonic development do not

argue for the role of intelligent design, rather than evolution, in the

formation of the structures of a new human life. The intricacies of the

human genome, with its 6 billion base pairs of DNA encoding an estimated

100,000 genes, can also be taken as an argument for intelligent design.

Proponents of intelligent design often compare the DNA sequence of the genome

to a computer program, powerful and flexible and carefully designed. Surely

the chance forces of evolution could not assemble so much purposeful complexity,

and surely the very sequences of human DNA argue for intelligent design.

Evolution as a Creative Force

Intelligent-Design advocates content that evolution could not have produced

such complex structures and processes because its instrument, natural selection,

simply isn't up to the tast. Such advocates agree that natural selection

does a splendid job of working on the variation that exists within a species.

Given a range of sizes, shapes, and colors, those individuals whose characteristics

give them the best chance to reproduce will pass on traits that will increase

in frequency in the next generation. The real issue, therefore, is whether

or not the "input" into genetic variation, which is often said

to be the result of random mutation, can provide the beneficial novelty

that would be required to produce new structures, new systems, and even

new species. Could the marvelous structures of the eye have been produced

"just by chance?"

The simple answer to that question is "no." The extraordinary

number of physiological and structural changes that would have to appear

at once to make a working, functioning eye is simply too much to leave to

chance. The eye could not have evolved in a single event. That, however,

is not the end of the story. The real test is whether or not the long-term

combination of genetic variation and natural selection could indeed produce

a structure as complex and well-adapted as the eye, and the answer to that

question is a resounding "yes."

The pathway by which evolution can produce such structures has been explained

many times, most recently in Richard Dawkins' extraordinary book, The

Blind Watchmaker. The essence of Dawkins' explanation is simple. Given

time (thousands of years) and material (millions of individuals in a species),

many genetic changes will occur that result in slight improvements

in a structure or system. However slight that improvement, so long as it

is a genuine improvement, natural selection will favor its spread throughout

the species over several generations.

Little by little, one improvement at a time, the system becomes more and

more complex, eventually resulting in the fully-functioning, well-adapted

organ that we call the eye. The retina and the lens did not have to evolve

separately, because they evolved together. As Dawkins is careful

to point out, this does not mean that evolution can account for any imaginable

structure, which may be why living organisms do not have biological wheels,

X-ray vision, or microwave transmitters.

But evolution can be used as an explanation for complex structures, if we

can imagine a series of small, intermediate steps leading from the simplex

to the complex. Further, because natural selection will act on every one

of those intermediates, these intermediate steps cannot be justified on

the basis of where they are going (the final structure). Each step must

stand on its own as an improvement that confers an advantage on the organism

that possesses it.

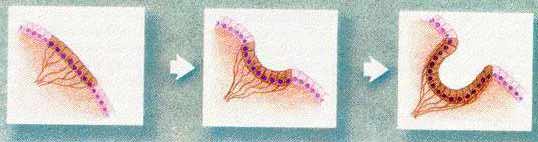

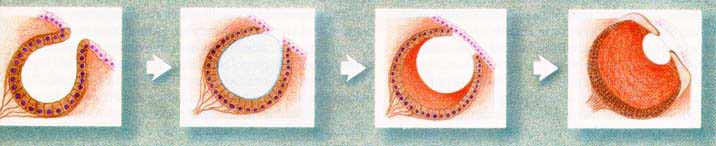

Evolution of the eye: A complex eye could easily have evolved from a simple eyespot through a series of minor and reasonable variations. When a change conferred even a slight advantage, it would have spread throughout the population over several generations.  |

This step-by-step process is the real reason why

it is unfair to characterize evolution as "mere chance," even

though chance plays a role in it. The continuing power of natural selection

fine-tunes each stage of the process in a way that is not determined by

chance. Can we apply this step-by-step criterion to a complex organ like

the eye? Yes, we can, quite easily in fact. We can begin with the simplest

possible case, a small animal with a single light-sensitive cell. We can

then ask, at each stage, whether natural selection would favor the incremental

changes that are shown, knowing that it if would not, the final structure

could not have evolved, no matter how beneficial.

Starting with the simplest light-sensing device, a single photoreceptor

cell, it is easy to draw a series of incremental changes that would lead,

step-by-step, directly to lens-and-retina eye. None of the intermediate

stages requires anything more than an incremental change in structure: an

increase in cell number, a change in surface curvature, a slight increase

in transparency. Therefore, all the changes are reasonable.

The critic might ask what good that first tiny step, perhaps only 5% of

an eye, might be. As the saying goes, in the land of the blind, the one-eyed

man is king. In a population with limited ability to sense light, every

slight improvement is favored, even if it represents only 5% of an eye.

If each individual, incremental change would be favored by natural selection,

the whole sequence is would be favored as well. Since none of the steps

involves an unreasonable genetic change, the contention that evolution cannot

explain the evolution of a complex eye is refuted.

One might rightly claim, of course, that if this were really true, then

evolution should have driven the independent development of light-sensing

abilities in scores of organisms. Has it? In their 1992 review of the evolution

of vision, Michael F. Land and Russell D. Fernald cite evidence that primitive

eye-spot light-sensing systems have evolved independently as many as 65

times, and that more complex image-forming systems have evolved many times,

employing roughly 10 optically distinct image-formation mechanisms. In the

mollusks alone, distinct light-sensing systems exist that bear an uncanny

resemblance to each of the stages in our hypothetical scheme. Obviously,

each of these intermediates has to be considered reasonable if an organism

living today possesses it.

Flawed Designs

If we can account for the evolution of complex

structures by incremental advances, this might seem to leave us with no

way to distinguish design from evolution. Evolution, then, might

have produced such structures. But did it? In fact, there is a way

to tell. Evolution, unlike design, works by the modification of pre-existing

structures. Intelligent design, by definition, works fresh, on a clean sheet

of paper, and should produce organisms that have been explicitly (and perfectly)

designed for the tasks they perform.

Evolution, on the other hand, does not produce perfection. The fact that

every intermediate stage in the development of an organ must confer a selective

advantage means that the simplest and most elegant design for an organ cannot

always be produced by evolution. In fact, the hallmark of evolution is the

modification of pre-existing structures. An evolved organism, in short,

should show the tell-tale signs of this modification. A designed organism

should not. Which is it?

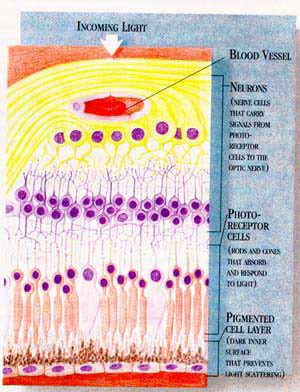

The eye, that supposed paragon

of intelligent design, is a perfect place to start. We have already sung

the virtues of this organ, and described some of its extraordinary capabilities.

But one thing that we have not considered is the neural wiring of its light-sensing

units, the photoreceptor cells in the retina. These cells pass impulses

to a series of interconnecting cells that eventually pass information to

the cells of the optic nerve, which leads to the brain. Given the basics

of this wiring, how would you orient the retina with respect to the direction

of light? Quite naturally, you (and any other designer) would choose the

orientation that produces the highest degree of visual quality. No one,

for example, would suggest that the neural wiring connections should be

placed on the side that faces the light, rather than on the side away from

it. Incredibly, this is exactly how the human retina is constructed.

The eye, that supposed paragon

of intelligent design, is a perfect place to start. We have already sung

the virtues of this organ, and described some of its extraordinary capabilities.

But one thing that we have not considered is the neural wiring of its light-sensing

units, the photoreceptor cells in the retina. These cells pass impulses

to a series of interconnecting cells that eventually pass information to

the cells of the optic nerve, which leads to the brain. Given the basics

of this wiring, how would you orient the retina with respect to the direction

of light? Quite naturally, you (and any other designer) would choose the

orientation that produces the highest degree of visual quality. No one,

for example, would suggest that the neural wiring connections should be

placed on the side that faces the light, rather than on the side away from

it. Incredibly, this is exactly how the human retina is constructed.

What are the consequences of wiring the retina backwards? First, there is

a degradation of visual quality due to the scattering of light as it passes

through layers of cellular wiring. To be sure, this scattering has been

minimized because the nerve cells are nearly transparent, but it cannot

be eliminated, because of the basic flaw in design. This design flaw is

compounded by the fact that the nerve cells require a rich blood supply,

so that a network of blood vessels also sits directly in front of the light-sensitive

layer, another feature that no engineer would stand for. Second, the nerve

impulses produced by photoreceptor cells must be carried to the brain, and

this means that at some point the neural wiring must pass directly through

the wall of the retina. The result? A "blind spot" in the retina,

a region where thousands of impulse-carrying cells have pushed the sensory

cells aside, and consequently nothing can be seen. Each human retina has

a blind spot roughly 1 mm in diameter, a blind spot that would not exist

if only the eye were designed with its sensory wiring behind the

photoreceptors instead of in front of them.

Do these design problems exist because it is impossible to construct an

eye that is wired properly, so that the light-sensitive cells face the incoming

image? Not at all. Many organisms have eyes in which the neural wiring is

neatly tucked away below the photoreceptor layer. The squid and the octopus,

for example, have a lens-and-retina eye quite similar to the vertebrate

one, but these mollusk eyes are wired right-side-out, with no light-scattering

nerve cells or blood vessels above the photoreceptors and no blind spot.

None of this should be taken to suggest that the eye functions poorly. Quite

the contrary, it is a superb visual instrument that serves us exceedingly

well. To support the view that the eye was produced by evolution, one does

not have to argue that the eye is defective or shoddy. Natural selection,

after all, has been fine-tuning every organ in the body, including the vertebrate

eye, for millions of years. The key to the argument from design is not whether

or not an organ or system works well, but whether its basic structural plan

is the obvious product of design. The structural plan of the eye is not.

Evolution, which works by repeatedly modifying preexisting structures, can

explain the inside-out nature of the vertebrate eye quite simply. The verterbate

retina evolved as a modification of the outer layer of the brain. Over time,

evolution progressively modified this part of the brain for light-sensitivity.

Although the layer of light-sensitive cells gradually assumed a retina-like

shape, it retained its original orientation, including a series of nerve

connections on its surface. Evolution, unlike an intelligent designer, cannot

start over from scratch to achieve the optimal design.

Tinkering with Success: the Mark of

Evolution

The living world is filled with examples of organs and structures that clearly

have their roots in the opportunistic modification of a preexisting structure

rather than the clean elegance of design. Steven Jay Gould, in his famous

essay "The Panda's Thumb," makes exactly this point. The giant

panda has a distinct and dexterous "thumb" which, like our own

thumb, is opposable. These animals nimbly strip the leaves off bamboo shots

by pulling the shoots between thumb and their five other fingers.

Five? No, the panda doesn't have six fingers, because it's thumb isn't a

true digit at all. In fact, it grips the shoot of bamboo between its palm

and a bone in the wrist which, in giant pandas, has been enlarged to form

a stubby protuberance.

A true designer would have been capable of remodeling a complete digit,

like the thumb of a primate, to hold the panda's food. Evolution, on the

other hand, settled for much less: a bamboo-gripping pseudo-digit that conferred

just enough of an advantage to be favored by natural selection. As Gould

himself notes, a single mutation increasing the rate of growth of this wristbone

could explain the formation of the Panda's "thumb." Natural selection

itself explains how this simple modification was advantageous. It is a clear

case of the way in which evolution produces organisms that are well-adapted,

but not necessarily well-designed.

A true designer could begin with a clean sheet of paper, and produce a design

that did not depend, as evolution must, on re-using old mechanisms, old

parts, and even old patterns of development. The use of old developmental

patterns is particularly striking in human embryonic development. The early

embryos of reptiles and birds, which produce eggs containing massive amounts

of yolk, follow a particularly specialized pattern of development. This

pattern enables them to produce the three vertebrate body layers in a disc

of cells that sits astride a hugh sphere of nutritive yolk. They eventually

surround that yolk with a "yolk sac," a layer of cells that supplies

the embryo with nutrition from the stored yolk.

Placental mammals produce tiny eggs, so there would be no need to follow

a developmental pattern that surrounds the non-existent mass of yolk. Nevertheless,

as Scott F. Gilbert, the author of an influential book on developmental

biology notes:

"What is surprising is that the gastrulation movements of reptilian

and avian embryos, which evolved as an adaptation to yolky eggs, are retained

even in the absence of large amounts of yolk in the mammalian embryo. The

inner cell mass can be envisioned as sitting atop an imaginary ball of yolk,

following instructions that seem more appropriate to its ancestors."

Indeed, human embryos even go so far as to form an empty yolk sac,

surrounding that non-existent stored food. The human yolk sac develops from

the same tissues as the yolk sacs of reptiles and birds, performs many of

the same functions (except, of course, for using the non-existent yolk),

and gives rise to the same adult tissues. That it why it has been known

as a "yolk sac" for more than a century. The cells of the sac

channel nutrients to the embryo (much as they do in birds and reptiles),

and play a role in the formation of the circulatory, reproductive, and digestive

systems. These functions do not explain, however, why the cells that

perform them should take the form of a sac.

There is no reason, from the standpoint of intelligent design, for the human

embryo to produce an empty yolk sac. Evolution, of course, can supply the

answer. If placental mammals are descended from egg-laying animals, like

reptiles, then the empty yolk sac can be understood as a evolutionary remnant.

The yolk sac is produced by a process of development that could not be re-designed

simply because mammalian eggs had lost their yolk. It suggests that mammals

evolved from animals that once had eggs with large amounts of yolk. Does

the historic fossil record support that contention? Absolutely. The very

first recognizable mammals in the fossil history of life on Earth are known

by a telling name: they are the "reptile-like mammals."

Hints of the Past

The concept of intelligent design is particularly clear on one point: organisms

have been designed to meet the distinct needs of their lifestyles and environments,

not to reflect an evolutionary history. Is this distinction between evolution

and design testable? I think it is, and the test is a simple one. Intelligent

design dictates that the genetic system of a living organism should be constructed

to suit its present needs, and should not contain superfluous genes or gene

sequences that obviously correspond to structures or substances for which

the organism has no need. In short, the master genetic plan should correspond

precisely to the organism for which it codes.

No living bird has teeth, and that fact, of course, is behind the old saying

that a rare object is "as scarce as hen's teeth." Why don't birds

have teeth? A proponent of intelligent design must answer that they have

not been designed to have teeth, quite probably because the designer

equipped them with alternatives (hard beaks and food-grinding gizzards)

that are superior for lightweight flying organisms.

Is this in fact the case? In 1980 Edward Kollar and his colleague C. Fisher

decided to test whether or not chicken cells still have the capacity

to become teeth. Intelligent design would predict that they cannot, because

teeth were never designed into the organism.

Kollar & Fisher's experiment was simple. They took mouse tissue that

normally lies just beneath the epithelial cells that develop into teeth,

and put it in contact with chick epithelial cells. What happened? The chick

cells, apparently influenced by the mouse tissue, dutifully began to develop

into teeth. The produced impact-resistant enamel on their surfaces, and

developed into clear, recognizable teeth (Figure 5). The experimenters took

great care to exclude the possibility that mouse tissue had produced the

teeth, first by making sure that no mouse epithelium was included in the

experiments, and second by confirming that the cells in the tooth-producing

tissue were indeed chick cells. Their experiments have since been confirmed

by two independent groups of investigators.

No plan of intelligent design can account for the presence of tooth-producing

genes in chicken cells. Indeed, it would be remarkably un-intelligent to

endow birds with such useless capabilities. Evolution, on the other hand,

has a perfectly good explanation for these capabilities. Birds are descended

from organisms that once had teeth, and therefore they may retain these

genes, even if other genetic changes normally turn their expression off.

In short, birds have a genetic mark of their own history that no designed

organism should ever possess. Designed organisms, after all, do not have

evolutionary histories.

The Story in DNA

In today's world, it is possible to test evolution and intelligent design

as never before. Rather than depending upon the indirect evidence of structure

and physiology, we can go right to the source to the genetic code itself.

If the human organism is, indeed, the product of careful, intelligent design,

a detailed analysis of human DNA should reveal that design. Remember the

quotation from Of Pandas and People: "We cannot build a palace by tinkering

with a tool shed and adding bits of marble piecemeal here and there. We

have to begin by devising a plan for the palace that coordinates all the

parts into an integrated whole." We can test intelligent design simply

by examining the genome to see if it matches the prediction of a coordinated,

integrated plan.

If, on the other hand, the human genome is the product of an evolutionary

history, that DNA should be a patchwork riddled with duplicated and discarded

genes, and loaded with hints and traces of our evolutionary past. This,

too, can be tested by directly examining the coded sequences of human DNA.

Although a complete sequence for all human DNA is at least a decade away,

we already know more than enough of that sequence to begin to address the

question of design. Let's take, as a representative example, a piece of

chromosome # 11 known as the b -globin cluster. About 60,000 DNA "bases"

are in the cluster, each base effectively representing 1 letter of a code

that contains the instructions for assembling part of a protein. b -globin

is an important part of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein that gives

blood its red color. There are 5 different kinds of b -globin, and the cluster

contains a gene for each one .

Why are there so many different forms of the b -globin gene? Here both evolution

and intelligent design could supply an answer. Two of the genes are expressed

in adults, and the other three are expressed during embryonic and fetal

development. Evolution maintains that the multiple copies have arisen by

gene duplication, a random process in which mistakes of DNA replication

resulted in extra copies of a single ancestral gene. Once the original b

-globin gene had been duplicated a number of times, so the explanation goes,

slight variations within each sequence could produce the 5 different forms

of the globin gene.

Why would different forms of b -globin be useful? The embryo, which is engaged

in a tug-of-war for oxygen with its mother, must have hemoglobin that binds

oxygen more tightly than the mother's adult hemoglobin. The 3 versions of

the gene that are expressed during embryonic development enable hemoglobin

to do exactly that. These slight variations enable embryonic blood to draw

oxygen out of the maternal circulation across the placenta into its own

circulation. Hence, gene duplication provided a chance for special forms

of the b -globin gene to evolve that are expressed in fetal development.

Intelligent design proposes much the same mechanism, except that the production

of extra copies and their modification to suit the embryo were a matter

of intentional design, not chance and natural selection. Intelligent design

maintains that the DNA sequences of each of the 5 genes of the cluster are

matters of engineering, not random gene duplications fine-tuned by natural

selection. So which is it? Are the 5 genes of this complex the elegant products

of design, or a series of mistakes of which evolution took advantage?

The cluster itself, or more specifically a sixth b -globin gene, provides

the answer. This gene is easy to recognize as part of the globin family

because it has a DNA sequence nearly identical to that of the other five

genes. Oddly, however, this gene is never expressed, it never produces a

protein, and it plays no role in producing hemoglobin. Biologists call such

regions "pseudogenes," reflecting the fact that however much they

may resemble working genes, in fact they are not.

How can we be sure the sixth gene really is a pseudogene? Molecular biologists

know that the expression of a gene like b -globin is a two-step process.

First, the DNA sequence has to be copied into an intermediate known as RNA.

That RNA sequence is then used to direct the assembly of a polypeptide,

in this case, a b -globin. There is no evidence that the first step ever

takes place for the pseudogene. No RNA matching its sequence has ever been

found. Why? Because it lacks the DNA control sequences that precede the

other 5 genes and signal the cell where to start producing RNA This means

that the pseudogene is "silent." Furthermore, even if it were

comehow copied into RNA, it still could not direct the assembly of a polypeptide.

The pseudogene contains 6 distinct defects, any one of which would prevent

it from producing a functional polypeptide. In short, this sixth gene is

a mess, a nonfunctional stretch of useless DNA.

From a design point of view, pseudogenes are indeed mistakes. So

why are they there? Intelligent design cannot explain the presence of a

nonfunctional pseudogene, unless it is willing to allow that the designer

made serious errors, wasting millions of bases of DNA on a blueprint full

of junk and scribbles. Evolution, however, can explain them easily. Pseudogenes

are nothing more than chance experiments in gene duplication that have failed,

and they persist in the genome as evolutionary remnants of the past history

of the b -globin genes.

The b -globin story is not an isolated one. Hundreds of pseudogenes have

been discovered in the 1 or 2% of human DNA that has been explored to date,

and more are added every month. In fact, the human genome is littered with

pseudogenes, gene fragments, "orphaned" genes, "junk"

DNA, and so many repeated copies of pointless DNA sequences that it cannot

be attributed to anything that resembles intelligent design.

If the DNA of a human being or any other organism resembled a carefully

constructed computer program, with neatly arranged and logically structured

modules each written to fulfill a specific function, the evidence of intelligent

design would be overwhelming. In fact, the genome resembles nothing so much

as a hodgepodge of borrowed, copied, mutated, and discarded sequences and

commands that has been cobbled together by millions of years of trial and

error against the relentless test of survival. It works, and it works brilliantly;

not because of intelligent design, but because of the great blind power

of natural selection to innovate, to test, and to discard what fails in

favor of what succeeds. The organisms that remain alive today, ourselves

included, are evolution's great successes.

A Process Set in Motion

It is crucial to recognize the stakes of this debate. "Intelligent

design theory" requires that we pretend to know less than we do about

living organisms and that we pretend to know less than we do about design,

engineering, and information theory. It demands that we set aside evolution's

simple and logical explanations for the design flaws of living organisms

in favor of a nebulous theory that pretends to account for everything by

stating "well, that's the way the designer made it." In short,

it requires a retreat back into an unknowledge of biology that is unworthy

of the scientific spirit of this century.

It is particularly unfortunate that the advocates of intelligent design

theory seem to see it as a way of countering what they view as evolution's

inherent incompatibility with religion. In reality, evolution is not at

all inconsistent with a belief in God, a fact recognized by Darwin himself

in the concluding passage of Origin of Species:

"There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers,

having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into

one; and that. whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed

law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful

and most wonderful have been and are being evolved."

William Paley once hoped that the study of life could tell us something

about the personality of the creator. Although Paley was wrong about the

argument from design, he may have been right about the issue of personality.

It seems to me that the scope and scale of evolution can only magnify our

admiration for a creator who could set such a process in motion. To the

deeply religious, evolution may not be seen as a challenge, but rather as

proof of the power and subtletly of the creator's ways. The great Architect

of the universe might not have written down each DNA base of the human genome,

but He would still be a very clever fellow indeed.